In The Amazing Aventures of Kavalier & Clay, Michael Chabon celebrates the Golem of Prague, shaped from the clay of the River Moldau as a “Recipe for Life.” The graphic geniuses of our story, cousins Sammy Clay and Joe Kavalier, make an indelible contribution to the Golden Age of the super hero comic book—under the spell of the golem.

The model for the first golem was Adam. In the Bible, on the sixth day of creation, the inspiration of the Divine Name was breathed into his nostrils, releasing him from his primordial lump of clay into the Garden of Eden. Since only God may generate perfect life, the making of a golem is dangerous territory. It is only the most pious and righteous tzaddiks (spiritual superheroes), learned in the mystical Kabbalah, who undertake this ritual—and only for the purposes of good.

Even so, all golems are ultimately flawed, without the power of speech or a soul. Inevitably, they are doomed to turn on their masters. Chabon, quoting the “golem hunter,” Gershom Scholem wrote, “Golem-making is dangerous…Like all major creation it endangers the life of the creator—the source of danger, however, is not the golem…but the man himself.”

In the many, variant recipes for making a golem, the body is shaped from clay, mud, or ash. Then, the inanimate humanoid is brought to life by the application of magical amulets, mystical incantations, reciting the names of God, or intoning the letters of the Hebrew alphabet just as God created the world in the Kabbalistic Book of Creation. The most storied formula is the application of the Hebrew word emet (truth) to his lifeless forehead or under his limp, gray tongue.

Historically, legends of golems as defenders of persecuted Jews first proliferated in the Middle Ages, especially at Passover, when accusations of Blood Libels (an anti-Semitic belief that Jews kidnapped and murdered the children of Christians to use their blood as part of their religious rituals) were widespread. A cycle of retaliation would ensue: beatings, burnings, pogroms, and then counter-attack by the local golem.

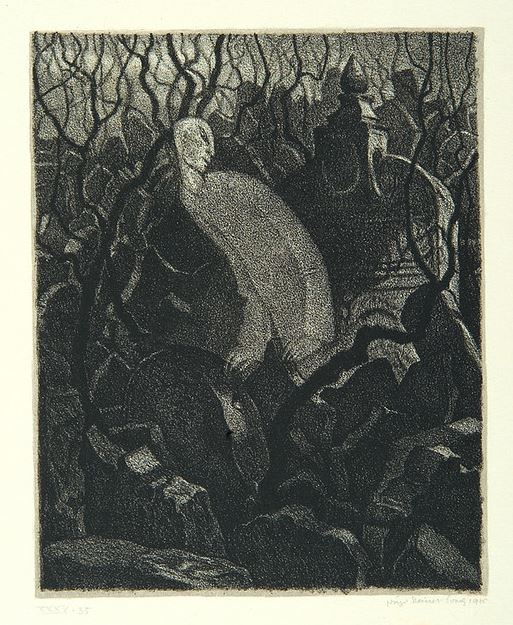

The geneology of the most famous golems dates back to late-16th-century Prague. This creature was born under the auspices of the Rabbi Judah Loew Ben Bezalel, also known as the Maharal of Prague, who is said to have created an exceptionally powerful defender of the ghetto denizens. A popular retelling of Rabbi Loew’s golem sagas features Yossele (Josef) who could not only sweep streets, split wood, make himself invisible, but also summon spirits from the dead. He was tireless and uncomplaining, until one Sabbath, Loew failed to deactivate his servant. Even a golem must be allowed a day to rest. Yossele went berserk, ripping up trees and destroying forests and fields—and desecrating the Shabbos.

Once Yossele wreaked his havoc, the rabbi had no choice but to destroy the work of his hands, returning it back to primordial mud. Just as he was brought to life, the creature’s destruction was accomplished by removing the letter alef from the word emet, leaving the word met (“dead”).

That golem’s body was stored in the attic of the Old New Synagogue, where he could be restored to life again, if needed. A recent story tells of a Nazi agent scaling the walls of the synagogue in an attempt to annihilate the golem forever. Chabon’s golem is hidden in a traveling casket, sleeping until he is teased into life again through the agency of our two New-World superhero comic book artists.

For Chabon, the making of a literary world brimming with life is analogous to the creation of a golem—by “magic.”

[quote]“The adept [writer] handles the rich material, the rank river clay, and diligently intones his alphabetical spells, knowing full well the history of golems: how they break free of their creators, grow to unimaginable size and power, refuse to be controlled. In the same way, the writer shapes his story, flecked like river clay with the grit of experience and rank with the smell of human life, heedless of the danger to himself, eager to show his powers, to celebrate his mastery, to bring into being a little world that, like God’s, is at once terribly imperfect and filled with astonishing life.”

—Michael Chabon, Washington Post Book World[/quote]

For Jews and non-Jews alike, the golem has been a popular figure in the arts. There are plays, musicals, movies, novels, operas, and even a ballet based on the golem legend. Famous among them are Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Karel Capek’s R.U.R. (origin of the word “robot”), I.B. Singer’s The Golem, and “The X-Files.”

Can you think of others?

Dramaturgy by Lenore Bensinger. The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay is on stage from June 8 – July 13.