by Little Bee Dramaturg Anthea Carns

There’s this quote¹ about writing fiction that I love, attributed to author Joe Haldeman:

[medium]“Bad books on writing tell you to ‘Write What You Know,’ a solemn and totally false adage that is the reason there exist so many mediocre novels about English professors contemplating adultery.”[/medium]

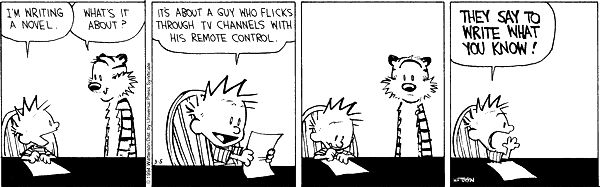

[Calvin knows what’s up.]

The maxim of “write what you know” has its roots in solid practice—an author writing about things she has done, places he’s been, feelings they’ve had or topics they’ve studied, will naturally bring a deeper sort of understanding to their work. They’ll be able to communicate with more truth and immediacy what their characters are going through when they and their characters have a shared experience.

As Haldeman points out, though, if the only thing people who have devoted their lives to writing can write about is what they know, then we end up with an awful lot of novels that are just about writers and writers’ lives. (I mean, a lot of writers lead pretty interesting lives, to be sure—but still, a varied literary world this does not necessarily make.)

That said, things start to get tricky when writers start writing about very different perspectives, especially perspectives from different cultures than their own. For instance, in Little Bee, British author Chris Cleave takes on two distinctive narrative voices, both presumably very far from the internal landscape he knows as a straight white British man: one, Sarah, is a British mother in her thirties, and one, Little Bee, a Nigerian girl in her teens.

Opinions from reviewers and readers of Little Bee seem to be divided into two camps. Either Cleave inhabited these perspectives that were so different from his completely and compellingly, or it was glaringly obvious that the author was a man writing from a woman’s perspective and he shouldn’t even have tried.

Apart from the question of realism, or at least suspension of disbelief—a subjective topic if ever there was one—there’s a question of . . . let’s call it ethics. Is it cultural appropriation for a white man to tell the story of a Nigerian girl? Well, potentially, yeah. Okay, then how about the story of a white woman? If the white man grew up in Africa, does that make it okay? Is it unethical for a black South African writer to tell a story from the perspective of a white South African? For a straight woman to write about a gay man?

There’s no bright line, and no simple answer. It is an important question, that’s for sure: it’s easy to find male authors whose female perspectives read like they’ve never talked to a woman in their life, white authors who write other cultures in a way that makes it seem like they’ve never been further afield than a country club. Those stories can be harmful and hurtful, especially when they perpetuate various stereotypes and make cultures into commodities. And even if they’re not harmful, they can be really annoying.

[Like when Thomas Harris writes about LGBTQ people. Sigh.]

So with that in mind, “write what you know” seems like not such a bad idea. Writing what you don’t know is hard, and screwing it up is easy, and most authors really don’t want to accidentally write something harmful.

Still. To me, it seems like a shame to say that creative people can only create art about people just like them. What’s the point of writing fiction, creating worlds and stories that don’t exist, if you have to cut yourself off from perspectives that aren’t your own?

Author Rochita Loenen-Ruiz says of writing fiction:

[quote]I think of how engaging with the work means engaging with the world means engaging with other cultures and engaging with human beings. I think of how we are driven by this desire to know more and to explore more. We want to know, we want to understand, we want to see beyond our limited vision. We also know that we are limited … writers have become more aware of the need to approach the work with more mindfulness and care.[/quote]

[quote]…This does not mean to say that we should not criticize a work or speak out when we see cultures being exoticized or objectified. Indeed, it is because we speak out that we see a growing awareness and a reaching towards more mindfulness.[/quote]

The point of this post isn’t to pass judgment one way or another on Little Bee. I’ve got my own opinions on where Chris Cleave succeeds and where he fails, but I don’t think there’s one right answer. I leave it as an exercise for the reader and viewer, when they come see Book-It’s production, to make up their own minds. My goal here is more to keep us thinking about what stories we tell, whose stories we tell, and how we tell them.

There’s a balance to be struck, especially as writers and artists coming from places of privilege. The first thing we should do, as readers, is seek out and help amplify the voices of those who are writing what they know: seek out the voices of writers of color, of women, of LGBTQ writers. And then, when we venture beyond what we know—ideally with the help of people who do know the terrain intimately—we need to do so with thoughtfulness and with respect. Stories are powerful things, after all. We owe it to each other to handle them with care.

1. Please note I am breaking a different cardinal rule of writing by starting this blog post with a quote. You should never break the rules, but when you break them, break ’em good and hard.

Anthea Carns writes a blog and it’s pretty great.

Little Bee runs April 22-May 17, 2015. Tickets on sale now.