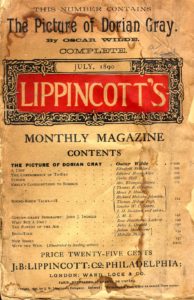

If you’ve read The Picture of Dorian Gray, you might think that Book-It’s upcoming adaptation is missing a few scenes. This script is adapted from the original typescript that Wilde submitted to Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, which was not published until 2011. This version is quite a bit different from the novel that most readers are familiar with and allows for refreshing new insight into this famous story.

If you’ve read The Picture of Dorian Gray, you might think that Book-It’s upcoming adaptation is missing a few scenes. This script is adapted from the original typescript that Wilde submitted to Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, which was not published until 2011. This version is quite a bit different from the novel that most readers are familiar with and allows for refreshing new insight into this famous story.

The editor of Lippincott’s, J.M. Stoddart, was shocked when he read Wilde’s typescript. Because of the controversy it would surely cause, Stoddart and his colleagues decided to proceed with caution:

“Rest assured that it will not go into the Magazine unless it is proper that it shall. In its present condition there are a number of things which an innocent woman would make an exception to. But I will go beyond this and make it acceptable to the most fastidious taste.”

Stoddart removed over 500 words, primarily those that were most explicitly sexual and homoerotic, in order to confine the novel’s contents to the acceptable limits of what could be published in 1890. Wilde was not informed of these changes before it went to the presses.

Despite Stoddart’s censorship, the story was sufficiently controversial. Reviewers condemned the “poisonous” and “unclean” story. Wilde counted 216 attacks on him in the press within the first two months. Britain’s largest bookseller, W.H. Smith & Son, pulled Lippincott’s from their shelves. Wilde spent the following months defending his work in the press. He wrote impassioned letters to newspapers that had run scathing criticisms of his work.

Wilde also began revising and expanding the story, which was published as a full novel in 1891. (If you’ve read The Picture of Dorian Gray, it was this version.) This version has nearly twice as many chapters, a greatly expanded cast of characters, and a vengeful villain. Dorian Gray is also a less sympathetic character, suggesting that Wilde may have caved somewhat to the novel’s moralistic critics.

Although this version of the novel is the most widely-read, many critics contend that the 1890 typescript is better representative of the story Wilde wanted to tell. When Wilde revised the story for the 1891 publication, he no longer had access to the original typescript, and had to work from the already-censored Lippincott’s edition. Furthermore, the editors of Ward, Lock, and Co. told Wilde to soften its sexual explicitness before they would publish it (and he had already been turned down by another publisher). Above all, Wilde wanted to avoid further public scrutiny. The reaction to the censored magazine edition had been so extreme that publishing the original text might have endangered him legally, so his self-censorship was an act of self-preservation.

This was shrewd, but it would not be enough to spare him later on. The Lippincott’s version of The Picture of Dorian Gray would resurface in 1895 during the trials that landed Wilde in prison for “gross indecency.” Lord Queensberry’s counsel read passages from the magazine version, rather than the “purged” novel edition, as evidence of the author’s immorality. After reading an incriminating passage during cross-examination, the counsel remarked:

COUNSEL: I believe it was left out in the purged edition?

OSCAR WILDE: I do not call it purged.

COUNSEL: Yes, I know that; but we will see.

Now you will see too. If you’re already familiar with The Picture of Dorian Gray, or if you’re experiencing it for the first time, we hope you can join us for the version of the story that was deemed too controversial for Victorian Readers. This is unabashed and uncensored Oscar Wilde at the peak of his career.

This post was written by dramaturg Ian Stewart. The Picture of Dorian Gray runs June 6-July 1 at The Center Theatre. Get your tickets today.