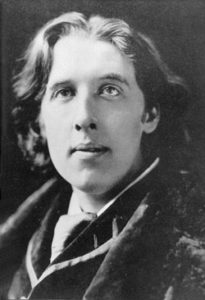

Oscar Wilde was born in Ireland. His mother was a respected radical poet who wrote dramatic lyrical poetry about Irish independence, the cruelty of English colonizers, and the oppression of women. When he came of age, Oscar received a scholarship to Trinity College in Dublin, and after three years he left Ireland to study Classics at Oxford. Not long after moving, he learned to pass among the English by shedding his Irish accent and lisp. Even as a young man, Oscar was recognizable as the man he would become: obsessed with art, disdainful of traditional morality, and sexually ambiguous.

Oscar Wilde was born in Ireland. His mother was a respected radical poet who wrote dramatic lyrical poetry about Irish independence, the cruelty of English colonizers, and the oppression of women. When he came of age, Oscar received a scholarship to Trinity College in Dublin, and after three years he left Ireland to study Classics at Oxford. Not long after moving, he learned to pass among the English by shedding his Irish accent and lisp. Even as a young man, Oscar was recognizable as the man he would become: obsessed with art, disdainful of traditional morality, and sexually ambiguous.

At Oxford, Oscar met his own personal Lord Henry Wotton: Walter Pater. While studying at Oxford, Oscar read Pater’s book Studies in the History of the Renaissance, which Oscar called his “golden book.” In this study of Renaissance art, Pater espoused the value of Art for Art’s sake. Most controversially, he wrote that the true end of life is “experience itself,” encouraging his readers to indulge in new experiences, and new pleasures. One can see how these ideas appealed to a young contrarian queer man like Oscar Wilde. Pater is the direct source for many of Lord Henry’s statements in The Picture of Dorian Gray.

By 1883, at age 29, Wilde was a moderately successful lecturer and writer who was constantly evading both moneylenders and persistent rumors of homosexuality. For Wilde, a middle-class artist, marriage to a rich woman might solve both problems. After courting a handful of women, he met and married Constance Lloyd the next year. Victorian masculinity was defined primarily by marriage, so marrying Constance allowed him to more easily live a double life.

Wilde launched his career by latching onto the Aestheticist movement, even though it was falling out of fashion. After graduating he developed a wide reputation as a flamboyant, witty Aesthete. Wilde even embarked on a sold-out speaking tour across the United States, where he gave news-making lectures on Aestheticism, fashion, and interior design.

In 1886, Wilde reached a turning point in his life when he lost his same-sex virginity to his friend Robert Ross. For once he felt truly able to act on his latent desires, and it even changed his outlook on himself: “After 1886 he was able to think of himself as a criminal, moving guiltily among the innocent”[1]. Over the next few years, he wrote essays and magazine articles on society, art, and culture, and fully developed his own version of Aestheticism. Almost single-handedly, he revived the Aestheticist movement.

This post was written by dramaturg Ian Stewart. The Picture of Dorian Gray runs June 6-July 1 at The Center Theatre. Get your tickets today. Read Part 2 here

[1] Ellmann, Richard. Oscar Wilde, 1988. Print. p. 278.