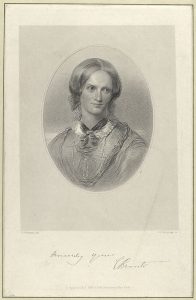

While Jane Eyre is widely regarded as a great work of art, the novel also reveals the progressive mind of author Charlotte Brontë amidst the societal limitations and expectations of women in the early 19th century. As a girl from a lower middle-class family, Charlotte’s options in life were limited from birth. Though not a radical feminist (she did not support a woman’s right to vote, for instance), her opinions and deep sense of self were, in themselves, radical for the time. Charlotte believed in marrying for love, a woman’s right to an education, the right to pursue a meaningful career, and held that respect was determined by a person’s work and actions, not their gender. These beliefs are inherent in Brontë’s titular heroine, though the author insisted that it was not penned as a self-portrait.

“It would startle him to see me in my natural home character; he would think I was a wild, romantic enthusiast indeed. I could not sit all day long making a grave face before my husband. I would laugh, and satirise, and say whatever came into my head first…I had not, and could not have, that intense attachment which would make me willing to die for him; and, if ever I marry, it must be in that light of adoration that I will regard my husband.” Charlotte Brontë, March 12, 1839

When Jane Eyre was written in the mid-1840s, established conservative gender roles placed women within the home with few rights or privileges. A woman’s individuality was typically undervalued and her capabilities underestimated. Women were considered physically inferior to men, yet morally superior. A man was allowed to be outspoken in his opinions, ambitious for an education, and venturesome in his workplace. It was acceptable (though never publicly or explicitly encouraged) for a man to be sexually passionate, while women were held to the opposite. Society expected women to aspire to become good wives and mothers, to practice restraint, follow “God’s path,” care for and be subservient to men, and always help others before themselves. The higher the class of woman, the greater the pressure to be guided by these “feminine principles.”

“Girls are protected as if they were something very frail and silly indeed, while boys are turned loose on the world as if they, of all beings in existence, were the wisest and the least liable to be led astray.” January 30, 1846

A woman was meant to pursue a husband without enthusiasm, which to the Victorians suggested a worrying sexual appetite. Romantic affairs of popular novels and works of poetry were seen as just that: highly romanticized. The purpose of marriage—for women—was to have children, not to seek emotional or physical satisfaction. In fact, William Acton famously wrote in his 1857 medical text that “the majority of women (happily for them) are not very much troubled with sexual feeling of any kind.” Those women who were passionate were labeled “mad” and frequently sent to languish in asylums or attics, locked away from civilized society.

“I know that if women wish to escape the stigma of husband-seeking they must act and look like marble or clay—cold, expressionless, bloodless…” April 2, 1845

Jane Eyre achieved near-instant success after publication, though to mixed reviews. Critics were aghast by the fantastical, impassioned nature of the novel, and the outspokenness of its heroine. The possibility that Jane Eyre was written by a woman caused possibly the harshest judgement. Though Charlotte upheld her male pen-name of Currer Bell years after her novels were published, rumor and speculation about the author’s gender were rampant. Denouncers called it “unfeminine” if the work of a woman, and if it were the work of a woman, “she must be a woman unsexed” and “had long forfeited the society of her own sex.” The hypocrisy of gender-based judgement at the time is evident in the review from the Economist of London: the male reviewer praised the book if written by a man, but deemed it “odious” if the work of a woman.

“As to society…If I were called upon to swap…tastes and ideas and feelings, I should prefer walking into a good Yorkshire kitchen fire, and conclude the bargain at once by an act of voluntary combustion.” January —, 1847

This dramaturgy was written by Jennifer Ewing. Jane Eyre runs Sept 13-Oct 14.