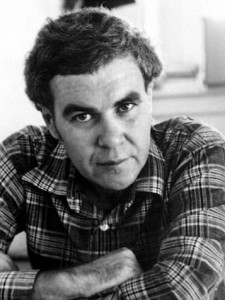

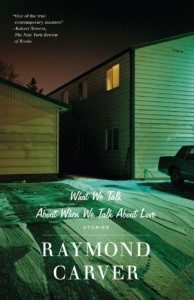

Raymond’s Carver reputation as a writer in the 1980s was rivaled by his reputation as a recovering alcoholic. The public eye fixed on his near-miraculous recovery and continued sobriety throughout the final decade of his life. Today he is considered one of the most important and influential short story writers of the 20th century. New details about Carver have sprouted from the cracks in the quarter century since his death, which have made my role as the dramaturg on Book-It’s upcoming What We Talk About When We Talk About Love all the more interesting. Book-It’s relationship with Raymond Carver is nearly as old as the company itself; a story by Raymond Carver was the second story Book-It ever staged (before they had even gained nonprofit status), and they previously mounted these four stories during their ninth season. But as the Book-It Style has developed and matured, so has the writer’s legacy, irrevocably altering the landscape of what we talk about when we talk about Raymond Carver.

What the *!#&%$ is a Dramaturg?

But let’s back up a bit, maybe you’re wondering, “What the hell is a dramaturg anyway?” Dramaturgs have become more and more common in theatres in recent decades, but I’ve found I have to explain my role to the non-initiated. Even then it’s hard to give a concise definition, because a dramaturg’s job can change drastically from one show to another. Generally, production dramaturgs are responsible for researching the world of the play and presenting pertinent information to the cast and creative team. On our upcoming production of Jane Austen’s Emma, for example, dramaturg Laura Owens is doing extensive research about the time period, its class tensions, and its expected manners, so the creative team can authentically realize Austen’s world. At Book-It, the dramaturgs also write program notes, attend rehearsals, create lobby displays, and write blog posts (like this one). A dramaturg is a lot like a lake dredger—something that drags things up to the surface for everyone to see. And every now and then, if the stars are aligned, it can also pull up a chunk of gold.

The process for a more familiar-feeling show like What We Talk About When We Talk About Love is a different kind of beast. Each of the stories takes place in the recent past, and its characters are people that everyone might know in real life. Unlike with Emma, the actors and creative team need little, if any, clarifying information to understand the world of the play. So if a dramaturg is like a lake dredger, what’s a dramaturg to do when everyone already knows what’s on the bottom of the lake?

Write What You Know

In my initial conversations with Jane, the director and adapter of the production, she introduced me to Carol Sklenicka’s massive biography Raymond Carver: A Writer’s Life. What we found inside was invaluable. Sklenicka frequently makes illuminating connections between the events in Carver’s life and the plots of his stories. It became clear how consistently Carver stuck to the old writers’ dictum “write what you know.” He wove many of his life’s most intimate details into his story, changing the specifics, but cutting close to his own heart. As I dove into the biography, I pulled out the biographical details that seemed most relevant to the four stories in our production. When I finished, my perception of the stories had been thoroughly turned over.

Jane and I found these connections so provocative that we brought them into the rehearsal room. During the rehearsal process, actors outline the “given circumstances” of the play to understand precisely where there characters are coming from. Actors in a romantic scene, for example, will want to know how long their characters have been together, what their favorite memories are, what their first date was like, and so on. But the script doesn’t provide all the answers; where there are gaps, actors and directors work together to invent circumstances that will fuel the action onstage.

With this show, Carver’s biography provided an abundance of circumstances for the actors to play with. “The fact that the two of us read the biography was inspiring,” Jane told me, “in terms of making the connections between his personal life and his stories.” In “The Student’s Wife,” a couple lies in bed late at night, but the wife is unable to go to sleep. Her smoldering restlessness is fueled by her constant stress over her family’s security, her full workload, and the lack of intimacy from her husband. This situation closely mirrors the early years of Ray’s marriage to Maryann, who worked full time to support her husband’s writing career while taking care of their two children. The actors found many ways to incorporate the details about the Carvers’ poverty, marriage, and work lives into their given circumstances, fleshing out their understanding of the characters while staying true to the author’s real experiences.

Beginners

Another gold nugget surfaced in the form of Carver’s original story manuscripts—drafts that Carver himself preferred to the published versions. Many of Carver’s stories, including “What We Talk About,” have had a controversial reception history because of the heavy involvement of Carver’s editor Gordon Lish, whose red pen acted more like a guillotine. Lish chopped out huge chunks of Carver’s stories, and struck out all but the bleakest passages. After reading about these extensive edits in the biography, I learned that Carver’s widow, Tess Gallagher, had worked to publish the original versions of all the stories in the collection as they’d been before Lish’s edits. The original manuscript of “What We Talk About,” called “Beginners,” is nearly twice as long as the published version and presents profoundly different versions of the characters and their alcohol-drenched conversation. When I brought “Beginners” to Jane, she read excerpts aloud in rehearsal that very evening. “Bringing in ‘Beginners’ gave us so much background on the characters and their given circumstances,” she says. Even though there are vast differences in the plot and characterizations in the two versions of the story, these differences allowed Jane and the actors to explore new possibilities for every moment that the published story had left unadorned.

I’d never experienced a dramaturgical process quite like this—one that required less time in the library and more direct involvement in the rehearsal room. It was especially exciting knowing that the same process wouldn’t have been possible when Book-It previously performed these stories in 1998, because the information we kept leaning on—the biography, recent criticism, and “Beginners”—simply didn’t exist 17 years ago. I see the difference as a testament to the power and intrigue of dramaturgy—that no matter how many times you dredge the same lake, there will always be new bits of gold to find.

Ian Stewart is one of Book-It’s 2015-16 Artistic interns. He is a 2015 graduate of the University of Oregon. You can hear him screaming into the void on Twitter @EeStew