Male Homosexuality in Victorian England

PUBLIC OPINION

Sex between men in Victorian England was an open secret. Everybody knew it happened but couldn’t directly refer to it in polite society or in newspapers. Nevertheless, it was a popular subject in fiction. Novels with coded homoerotic themes like The Picture of Dorian Gray flew off the shelves, even as major booksellers refused to stock them. Overall, public opinion on homosexuality in Victorian England was not as hateful as one might assume. Because homosexuality was such a taboo topic in public discourse, outright homophobia was less common than curiosity or indifference. Silence, loneliness, and shame were the most common oppressive forces among gay men and women, who for the most part could only suppress their sexuality. The condemnation of gay people and gay novels in the press was merely the rage of a small minority of rich conservatives who could afford to voice their opinions.

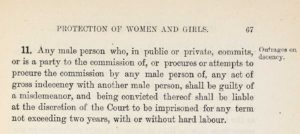

The legal system was more oppressive: in the early half of the 19th century sodomy carried the death penalty, and in the latter half it carried a life sentence. (Sodomy was defined as anal intercourse.) However, sodomy laws were difficult to enforce. The 1885 Labouchere Amendment changed that by also criminalizing “gross indecency” — meaning all male-male sex acts besides sodomy. Oscar Wilde would eventually be tried under the Labouchere Amendment in 1894. Despite these laws, actual charges were very rare; in fact, there was no significant increase in the number of sodomy charges throughout the entire 19th century in England. As far as law enforcement statistics go, the 20th century would prove to be far more oppressive.

CODED BEHAVIORS

In Victorian England, there were a number of styles, interests, and other traits associated with homosexuality, as there are today. Writers and artists used stereotypical traits to code certain characters as homosexuals. Some of these stereotypes have persisted to the modern day (limp wrists, lisps, “musical” young men). Others stereotypes seem inexplicable (crooked fingers, carnations). Even many innocent-seeming adjectives implied homosexuality: earnest, languid, sterile. Another stereotype was “camp” behavior, which many gay men used for practical reasons: they could use effeminate mannerisms, fashions, and expressions, then write them off as wry humor rather than actual expressions of homosexuality.

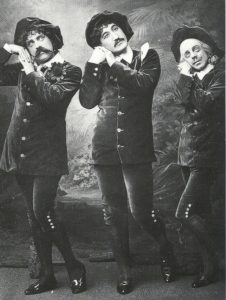

The Aesthetes of the late 19th century were a prime example of Victorian camp. Dressing in knee-breeches and flowers — most famously green carnations — they made beauty the object of their lives and their art. They were mocked constantly in the press, both affectionately and not-so-affectionately. Gilbert and Sullivan’s operetta Patience was entirely dedicated to making fun of the effeminate aesthetes. Looking at a photo from the performance it’s hard not to see what they were implying about the characters. Although sexuality (and especially homosexuality) could never be discussed publicly, the homosexual subtexts of the Aesthetes, and those who mocked them were well understood.

CLASS MATTERS

The Victorian upper class (the wealthiest 0.5%) were commonly viewed as hedonistic, amoral, and personally disloyal. Among the aristocracy, extramarital affairs were tolerated — so long as they didn’t cause a public scandal. Aristocratic men were classically educated, and therefore familiar with the tolerant depiction of homosexual sex in ancient Greek and Roman texts. The ancient Greeks and Romans provided a decent model for upper-class Victorian homosexuality: a model that was not effeminizing or damaging to one’s masculinity.

As the middle class grew and sought further influence, middle-class men looked for ways to distinguish themselves from upper class “hedonists”. Whereas the upper class derived their reputation from the opinions of others, middle-class men placed more importance on improving their own character through personal discipline and by adhering to religious and moral principles. And whereas the upper class believed that the pursuit of pleasure was an acceptable aim in life, the middle class feared that idleness and sin could ruin their precarious position in society. All this meant that middle-class men were more likely than the aristocracy to suppress or hide their homosexual desires.

ON THE STAND

During cross-examination at Oscar Wilde’s first trial, he was asked about a line in a poem that his lover Lord Alfred Douglas had written to him: “The love that dare not speak its name.” Wilde defined it for the court:

This post was written by dramaturg Ian Stewart. The Picture of Dorian Gray runs June 6-July 1 at The Center Theatre. Get your tickets today.